The waters off Somalia are some of the richest fishing grounds in the world and are still largely untapped. Following the steady decline in attacks by Somali pirates since 2012, foreign fishing fleets have gradually returned to Somali waters. Many of these vessels, particularly those originating in Iran, Yemen and South East Asia, routinely engage in IUU (illegal, unreported and unregulated) fishing practices.

Somalia is in the midst of its fourth decade of civil war and is routinely categorized as a ‘failed state’. The country has balkanized into a series of semi-autonomous regional administrations loosely overseen by a federal government located in the capital of Mogadishu. State institutions are extremely weak and corruption is widespread. Fishing licences and other permissions issued by one local Somali authority are often not recognized by another.

Domestically, the prevalence of foreign IUU fishing vessels has been frequently cited as a justification for acts of piracy by Somalia-based gangs. Somali pirates have instrumentalized this perception, casting themselves as defenders of Somali waters against foreign exploiters. However, the reality is far more nuanced. Foreign IUU fishing operations are frequently facilitated by local Somali agents, often in cooperation with government or quasi-governmental actors, who for a fee provide fishing licences, flag registrations, falsified export documentation and even armed onboard security detachments.

Private fishing operators vie for capture of state bodies in order to lend legitimacy to their IUU fishing operations. Decisions and authorizations issued by one state body are often countermanded by other agents of the state who are under the influence of a different set of private interests. IUU fishing in Somalia is in effect a public-private partnership in transnational crime.

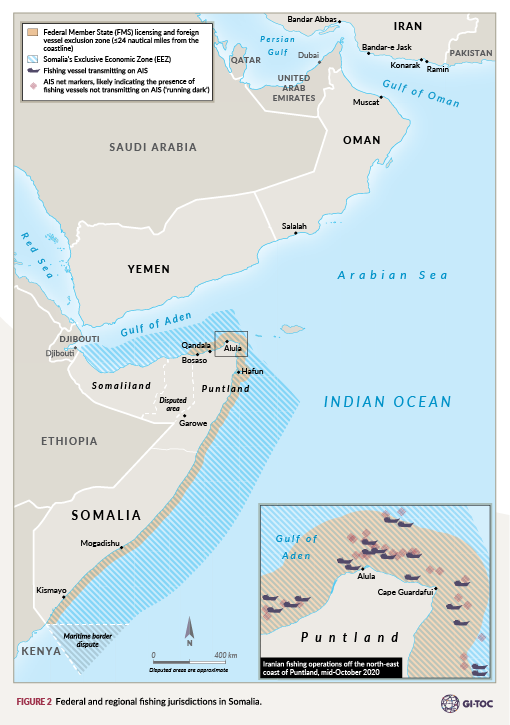

This paper will present three case studies of IUU fishing practices in Somalia, each illustrating a different facet of corruption within Somali state institutions. First, it will examine the environmentally destructive impact of the hundreds of Iranian gillnetters operating in the waters off Puntland, a semi-autonomous region of north-eastern Somalia. Facilitated by a cabal of local Somali fishing agents with ties to the Puntland Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, Iranian vessel owners have consistently obtained licences and armed local protection, despite the fact that the Puntland administration is not authorized to issue licences to foreign vessels.

Secondly, the paper will look at the case of the Marwan 1, a long-haul fishing trawler that once formed part of a notorious fleet of Thai IUU fishing vessels dubbed ‘The Somali 7’ by investigative journalist Ian Urbina. It will show how a Somali fishing agent based in Oman arranged to traffic a crew from Kenya that was later allegedly subjected to forced labour, inhumane working conditions and human rights abuses aboard the Marwan 1.

Finally, the paper will examine the case of the North East Fishing Company (NEFCO), a Somali fishing concern based in Puntland that has long enjoyed preferential treatment from local government officials. Beginning in late 2019, the company was able to engage directly with senior officials within the federal fisheries ministry – including the minister himself – to repeatedly issue irregular documentation to facilitate the company’s seafood exports to China. NEFCO company officers and officials in the fisheries ministry, including the minister, ultimately pursued a private initiative to sell Somali fishing rights through an entity they had jointly established.

In an effort to streamline the issuing of fishing licences and ensure the effective management of the country’s marine resource, Somalia’s federal government and the country’s regional administrations reached a provisional resource-sharing agreement with respect to the fisheries sector in Addis Ababa in March 2019. Yet the continued issuing of ‘licences’ by illegitimate authorities, in particular the Puntland administration, has badly undermined the implementation of the deal. With the Somali government’s limited ability to police the integrity of its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) or issue credible fishing licences, IUU fishing is likely to remain an attractive option for foreign fishing fleets.

Click the link below to read the full report

GITOC-ESAObs-Fishy-Business-Illegal-fishing-in-Somalia-and-the-capture-of-state-institutions